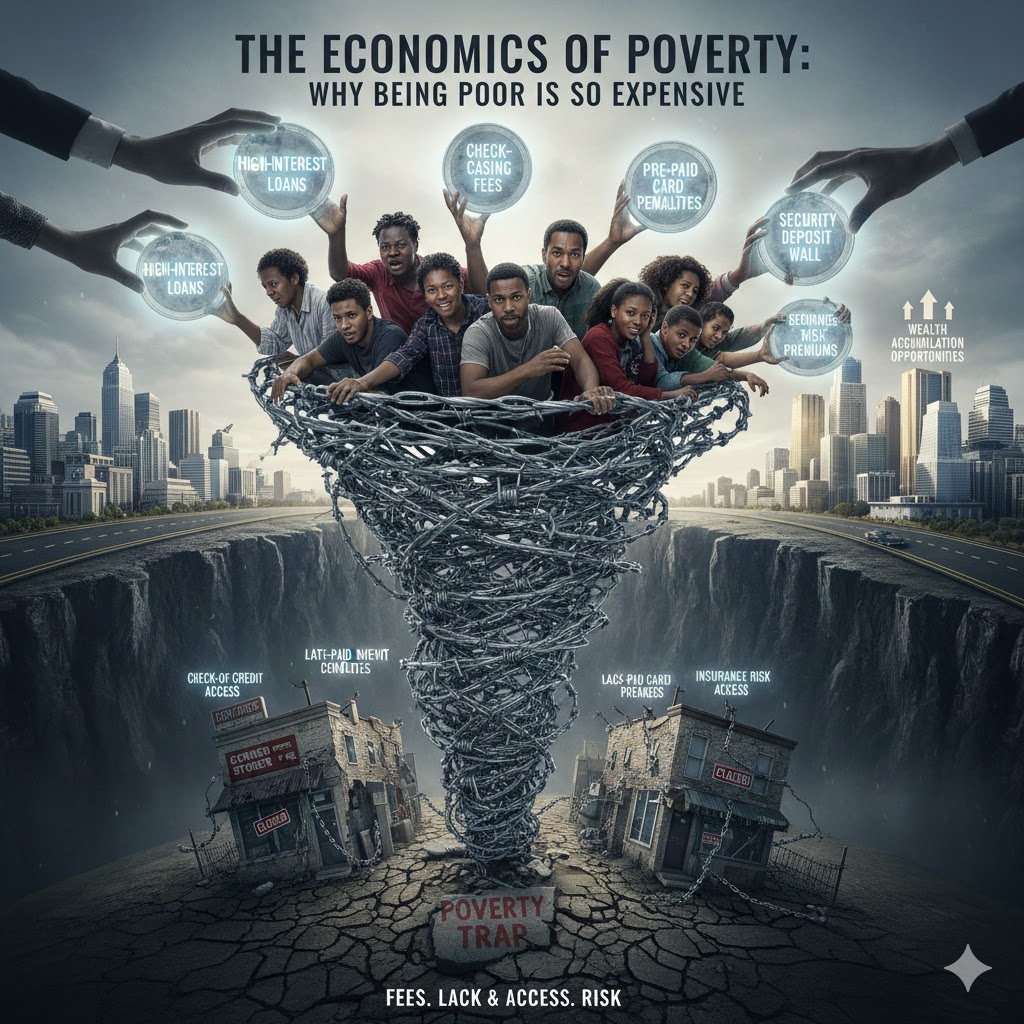

The Economics of Poverty: Why Being Poor Is So Expensive

By WealthQuizzes Editorial Team

Introduction: Poverty Is Not Just Low Income

Poverty is often described as a lack of money. In reality, it is far more complex—and far more costly.

Being poor is expensive. The poorest households and smallest businesses routinely pay more for basic goods, financial services, energy, transport, and risk than their wealthier counterparts. These higher costs are not accidental; they are embedded in how markets, institutions, and access systems function.

Understanding the economics of poverty requires moving beyond sympathy to structure—the mechanisms that trap people and enterprises in cycles they struggle to escape.

The Poverty Premium: Paying More for the Same Things

At the heart of poverty economics is what economists call the poverty premium: the extra cost poor people pay simply because they are poor.

Examples include:

- Higher interest rates on loans,

- Higher transaction fees for basic payments,

- More expensive energy sources,

- Costlier food purchases in smaller quantities,

- Greater exposure to fraud and exploitation.

This premium compounds over time, steadily eroding income and opportunity.

Financial Access: When Exclusion Becomes a Cost

Formal financial systems reward predictability and scale. Those without stable income, collateral, or credit histories are deemed “high risk”—and are charged accordingly.

Credit Costs

- Informal loans carry extremely high interest rates.

- Payday-style lending thrives where banks will not lend.

- SMEs without documentation face punitive borrowing terms.

As a result, capital—essential for growth—becomes prohibitively expensive.

Transaction Costs

Without access to efficient banking:

- People pay more to send and receive money,

- Small businesses lose margins to payment intermediaries,

- Savings are stored in unsafe, non-interest-bearing forms.

Lack of access transforms routine financial activity into a constant drain.

Risk Premiums: When Uncertainty Becomes a Tax

Poverty is closely linked to risk exposure—and risk is expensive.

Poor households face:

- Income volatility,

- Health emergencies without insurance,

- Insecurity and theft,

- Unstable housing and utilities.

Because they cannot absorb shocks, they must:

- Overpay for protection,

- Accept exploitative contracts,

- Avoid long-term planning.

In contrast, wealth absorbs risk cheaply—through insurance, diversification, and buffers.

Risk does not just follow poverty; it reinforces it.

Energy, Transport, and the Cost of Inefficiency

Infrastructure gaps create hidden costs that disproportionately affect the poor.

- Households without electricity rely on generators or kerosene—far more expensive per unit.

- Poor transport networks raise commuting costs and reduce job access.

- Inconsistent water supply forces reliance on private vendors at inflated prices.

These inefficiencies function like regressive taxes, paid daily by those least able to afford them.

Food Economics: Buying Small Is Buying Expensive

Low-income households often purchase goods in small quantities because they lack cash flow or storage.

This leads to:

- Higher unit prices,

- Reduced ability to stockpile during price dips,

- Greater vulnerability to inflation.

The irony is stark: those who need savings the most are least able to capture them.

Business Poverty: Why Small Enterprises Stay Small

The same dynamics apply to micro and small businesses.

SMEs face:

- Higher borrowing costs,

- Limited supplier credit,

- Poor bargaining power,

- Weak legal protection.

Without affordable capital and reliable infrastructure, productivity remains low. Low productivity keeps profits thin. Thin profits prevent reinvestment.

This is the enterprise poverty trap.

Time Poverty: The Hidden Multiplier

Poverty also consumes time.

- Long queues for basic services,

- Manual processes instead of automation,

- Travel to access distant facilities.

Time spent navigating inefficiency is time not spent earning, learning, or growing.

Time poverty quietly reduces lifetime income.

Why Markets Don’t Fix This Automatically

Left alone, markets price risk—not fairness.

Without:

- Inclusive financial infrastructure,

- Competition,

- Consumer protection,

- Scalable access tools,

the poverty premium persists.

This is why poverty is not simply an individual failure—it is a systemic outcome.

Breaking the Cycle: What Actually Reduces the Cost of Being Poor

Effective solutions reduce access costs, not just provide aid.

They include:

- Digital financial services with fair pricing,

- Credit models based on behavior, not collateral,

- Infrastructure investment that lowers unit costs,

- Formalization pathways for SMEs,

- Education that improves financial decision-making.

The goal is not charity—it is efficiency and inclusion.

African Context: Poverty as a Structural Cost Problem

Across Africa:

- Informal economies dominate,

- Financial exclusion remains high,

- Infrastructure gaps persist.

Yet innovation—especially in fintech, mobile money, and data-driven lending—is beginning to compress the poverty premium by lowering transaction costs and expanding access.

The challenge is scale, regulation, and literacy.

WealthQuizzes Perspective: Poverty Is an Economics Problem, Not a Moral One

At WealthQuizzes, we believe poverty should be analyzed—not moralized.

When people understand:

- Why access matters,

- How risk is priced,

- Where costs originate,

they are better equipped to make strategic choices and demand better systems.

Poverty is expensive because systems make it so.

Reducing poverty means reducing the cost of participation in the economy.

And that begins with understanding the economics behind it.

Because the first step to escaping a trap is knowing how it works.